Taking Care and Making Do

Finding Opportunity from Failure

Oliver Ray-Chaudhuri

i

Taking Care and Making Do

Finding Opportunity from Failure

Oliver Ray-Chaudhuri

Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Architecture (Professional) degree, The University of Auckland, 2023.

ii

iii

“Connaissez-vous, c’est toujours la vie qui a raison, l’architecte qui a tort.”1

(“You know, it is always life which is right, it is the architect who is wrong.”)

Le Corbusier

iv

v

Our lust for the new and improved risks exacerbating the impact of the building industry on climate emissions through unneces-sary demolition and reconstruction. This temptation is fuelled by a misconception of architecture as static and incapable of changing to meet today’s needs. Yet buildings continue to change far beyond their initial construction — architects are just one contributor among a complex network of actors who design, inhabit, damage, fix and alter buildings. This thesis asks how understanding existing ordinary buildings as perpetually unfinished assemblages could allow us to view reuse as a continuous process rather than a last-ditch transfor-mation of an already degraded shell. Using the author’s family home as a case study, an evolving process of representation considers how the practices of drawing and photography that currently reinforce a view of buildings as immutable could be reoriented to challenge this perception instead. The drawings highlight, through their gaps, defects and animation, possibilities for the inevitable maintenance and repair required of an older building to be used as opportunities for small acts of repair that do more than just return it to a perceived ‘original’ condition. This practice of ‘more-than-maintenance’ is tested in a series of interventions to the house and a public installation, which point towards the need for a broader reformulation of the role of the architect in our times of crisis.

Abstract

vi

vii

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Mum and Dad, for making anything possible.

Thank you to my supervisor Dorita Hannah, for your continual support. The research would not be what it is without the gaps of opportunity opened up by our conversations.

Thank you to the teaching staff at the UoA School of Architecture, especially Karamia Müller and Marian Macken for your guidance and encouragement.

Thank you to Philip Lee, Calvin Feng, Binh Minh Ha, Sarah Lin, Jack Wu, Gujin Chung, Ethan Chung, Dian Wang and Victoria Gancheva, for your company in studio and beyond.

viii

1

Introduction

The context for this thesis (like any research in the 21st century) is a world beset by crisis. Climate scientists have warned for decades about the impact of global warming caused by human activity, but today their previously abstract predictions and graphs feel increasingly tangible. In the midst of completing this project, the world experienced its hottest week on record.2 Seawater off the coast of Florida reached the temperature of a hot tub.3 Aotearoa New Zealand endured multiple bouts of catastrophic flooding.4 The world was literally on fire.5

By now, the impact of the building industry on climate change is well known. The construction and operation of buildings account for 39% of global emissions (in New Zealand, 20%).6 Architectural firms have acknowledged the crisis through updated website biographies, green accreditations and initiatives such as Aotearoa New Zealand Architects Declare, a “network of architectural practices committed to addressing the climate and biodiversity emergency.”7 Yet in most instances, recognition seems to be as far as the action goes. Signatories of Architects Declare continue to build some of New Zealand’s largest and most lavish skyscrapers, mansions, and holiday homes.

As an architectural graduate on the precipice of entering practice, it is hard not to feel a sense of helplessness about the inevitable burden of our work on an already suffocating planet. Regardless of rhetoric, intentions to ‘educate’ or embrace sustainable technologies, our disci-pline remains inseparable from the extravagant construction of large buildings. The premise of this research was a visceral reaction to my

2

uneasiness — how can we work with what we have instead of making new buildings?

The thesis asserts that it is only by repairing the systems and processes of the industry that we can achieve the change needed to reduce its significant impact on climate emissions. While it is essential to pursue scientific strategies to make new buildings more ‘green,’ we cannot rely on technology alone to save us. In this spirit, the research takes as its starting point the existing — the ways we view, represent, design, and live in buildings — and unfolds as an interrogation and reinterpretation of these assumptions.

My thinking developed through an intimate and ongoing engage-ment with the case study for the thesis: my family’s home in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, which serves as a sort of personal testing ground for its universal theories. The house is the subject of a practice of drawing which is used to consider how the representation of archi-tecture reinforces an insufficient view of buildings as ‘complete’ and immutable. This practice continues throughout the project as a means to experiment with ways of better capturing buildings as perpetually unfinished networks of tangible and intangible components.

The ongoing process and the accompanying research develop into a theory of more-than-maintenance, a way of seizing the failures of the everyday as opportunities for small acts of repair that do more than perpetuate the status quo. The practice is tested in a series of interventions to the house and then exposed to the contingencies of the real world in a public installation.

This document tells the story of the research, explaining in a rough chronology how my thinking developed throughout the year alongside the evolving representation. It is structured into six chapters which each incorporate discussions of relevant making, literature, prece-dents, and thinkers.

Chapter 1: Working with What We Have explains the importance of developing theories for reusing ordinary buildings as well as the extraordinary buildings that are the focus of the majority of the liter-ature. It introduces my family’s home as the case study of the thesis and recounts the first set of drawings, which are redrawn from the original documentation of the house.

Chapter 2: The Myth of Completion draws on Actor-Network Theory

3

and the work of other architectural scholars to establish buildings as perpetually unfinished networks composed of physical and social actors and altered by professionals and non-professionals alike. It discusses how a notion of completion is perpetuated through the representation and marketing of architecture, which reinforces a misconception of buildings as immutable and limits their capacity for appropriation. This establishes representation as the key means through which the thesis endeavours to redefine buildings as dynamic and alive and charts my early efforts to do this by introducing the messy inhabitation of the house into its plans, sections, and perspectives.

Chapter 3: Taking Care discusses the potential of maintenance and repair as tangible and deliberate commitments to the ongoing use of existing buildings. It explores how, as responses to failure, these practices tend to reinforce the status quo by restoring a building to a perceived normative (static) state. In contrast, failures (as intrusions on the fabric of everyday life) are posited as opportunities to challenge the otherwise unquestioned ways we live in buildings. This establishes the possibility of the second half of the project.

Chapter 4: Paying Attention explores how the representation of buildings using photogrammetry combines the detail of photography with some of the failure and inaccuracy present in a real building. It considers how this expanded representation could stimulate a broader scope of interventions within existing buildings by taking them outside of reality. These point cloud images serve as the basis for drawings which test this hypothesis, which are introduced here.

Chapter 5: Failure as Opportunity contains the core architectural proposal of this thesis, a series of interventions in the house developed through incremental additions to the point cloud drawings. These examples are used to establish the practice of more-than-maintenance, in which our responses to failure extend the longevity of an existing building while challenging the logic of its established socio-political condition.

Chapter 6: Making Do asserts the need to work beyond the confines of representation, borders and the systems that currently structure our neighbourhoods to realise the full potential of more-than-main-tenance. It describes the design and execution of a public installation which sought to encourage the social negotiation that is essential to

4

the theory yet impossible to simulate through drawing. Learnings from this installation are used to articulate an expanded role for the architect characterised by a continual engagement with and retreat from the reality of buildings in the everyday. The final crit is described as a reintroduction of the theory back into the world.

5

7

Working with What We Have

Chapter 1

As an existential threat, climate change compels action, but its vast scale is paralysing. The premise of this thesis — abstinence from the construction of new buildings — functions as a way to imagine the change that could be exerted at the scale of a single profession. It is more personal ‘thought experiment’ than pragmatic ‘solution.’ Yet it is a reaction shared by an increasing number of others as architectural thinkers grapple with the role of the building industry in the context of wider environmental collapse.

French architect and academic Charlotte Malterre-Barthes is call-ing for A Moratorium on New Construction. Her ongoing initiative includes a seminar at Harvard GSD and an upcoming book, which suggest that pausing new construction could create a “radical thinking framework for alternatives to the current regime of space production and its suspect growth imperative.”8 For Malterre Barthes, abstaining from building new is the only way to initiate the dramatic structural change needed to realise a non-extractive future.

Fig. 1-2. Provocations from Charlotte Malterre-Barthes’s research project A Moratorium on New Construction

8

Similarly, academics Christopher Grafe and Tim Rieniets advocate for the unconditional use of existing buildings as the resource for all future architecture. They recall a 1967 demonstration in Berlin during which students held a banner reading “All Buildings Are Beautiful; Stop Building More” to protest against what was seen as the careless demolition of historical structures in favour of mass housing. Grafe and Rieniets argue that today (as the postwar housing opposed by the students is demolished), this slogan should be interpreted as a “specific call to action for everyone who plays a role in shaping the built world of tomorrow.”9

Working with the Ordinary

Any shift towards the use of existing buildings is not without prec-edent. The discipline of heritage conservation has been evolving for centuries to define how we preserve old buildings. However, only a small minority of buildings are deemed worthy of conservation within the heritage framework. In New Zealand, the ICOMOS New Zealand Charter establishes principles for conserving places of cultural herit-age value.10 The value of a particular building is defined by its signif-icance, which is determined by assessing its relative worth across aesthetic, scientific, social and historical criteria.11 Heritage thinking has also served as the foundation for the comparatively recent practice of adaptive reuse, a process of “transforming an unused or underused building into one that serves a new use.”12 Although the adaptive reuse field does not share the same constraints as heritage conservation, it is still characterised in the popular imagination by the soaring ceilings and crumbling brickwork of vast industrial monuments.

The bulk of our building stock is not significant but boring and unremarkable. Working with what we have in the urgent context of the climate crisis therefore requires emphasising the ordinary as much as the extraordinary. This project adopts the ‘ordinary’ as its focus, a broad label encompassing all buildings that exist outside the

9

realm of significance as prescribed by the heritage field — the homes, offices and shops that form the background of our daily lives, rarely warranting a second look.

Fig. 3-4. Tree, pavements, houses and a cat in the suburbs.

10

Despite the unassuming ubiquity of ordinary buildings, they cannot be generalised into a homogeneous block — their immersion in the everyday means they are highly specific. This specificity is apparent on a second look, in the way a footpath veers around a tree, its roots forcing a break in the kerb, the particular way it casts its shadow on a timber fence. Everything is found to be unconventional when focus-ing more closely on the expected convention of the everyday. I used photography and video to record these anomalies within the fleeting moments of daily life. These images illustrate the thesis and served as a constant tool to observe the phenomena explored in the research.

The House

I decided that to properly grasp the specificity of the everyday, I needed to pay particularly close attention to a building that would not normally be the subject of close architectural investigation. I chose my family’s home in the suburbs of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland’s North Shore. The five-bedroom house is large, but quite ordinary. It was designed by architect John D’Anvers in 1984 and sits in the middle of a 1301m2 site lined by trees. A brick veneer base is topped with two floors clad in cedar weatherboards and an irregularly pitched roof. Inside, the rimu timber ceiling framing is left exposed.

We have lived in the house since 2007, soon after our arrival in New Zealand from the United Kingdom. It is my normal, a space I have an intimacy with like no other. Every room is saturated with memories and slight changes are obvious. My familiarity with the house meant I could investigate it with a freedom not possible with any other building. However, I did worry that I would take too much for granted — that my immersion would make it difficult to see the forest for the trees.

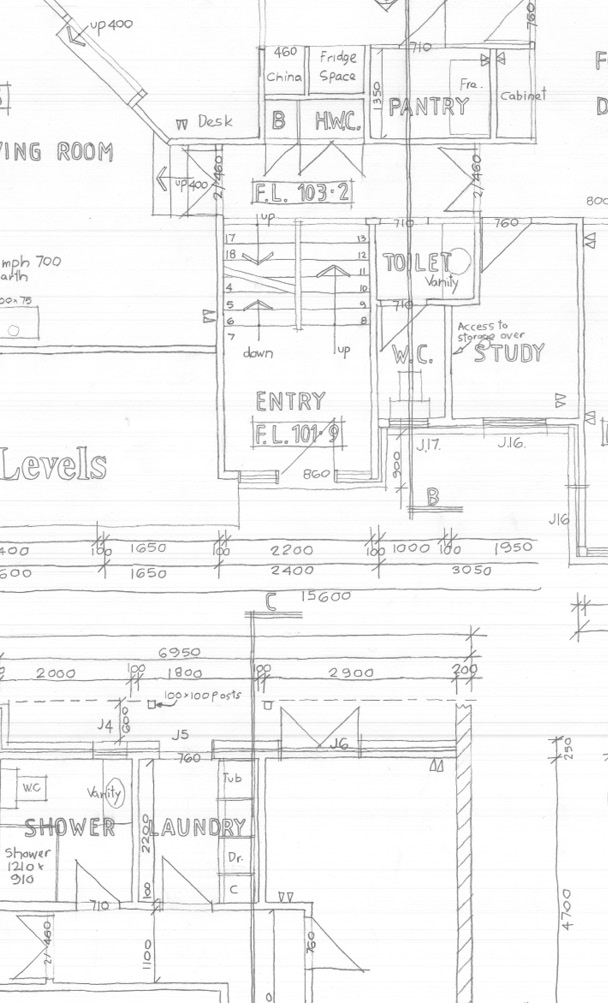

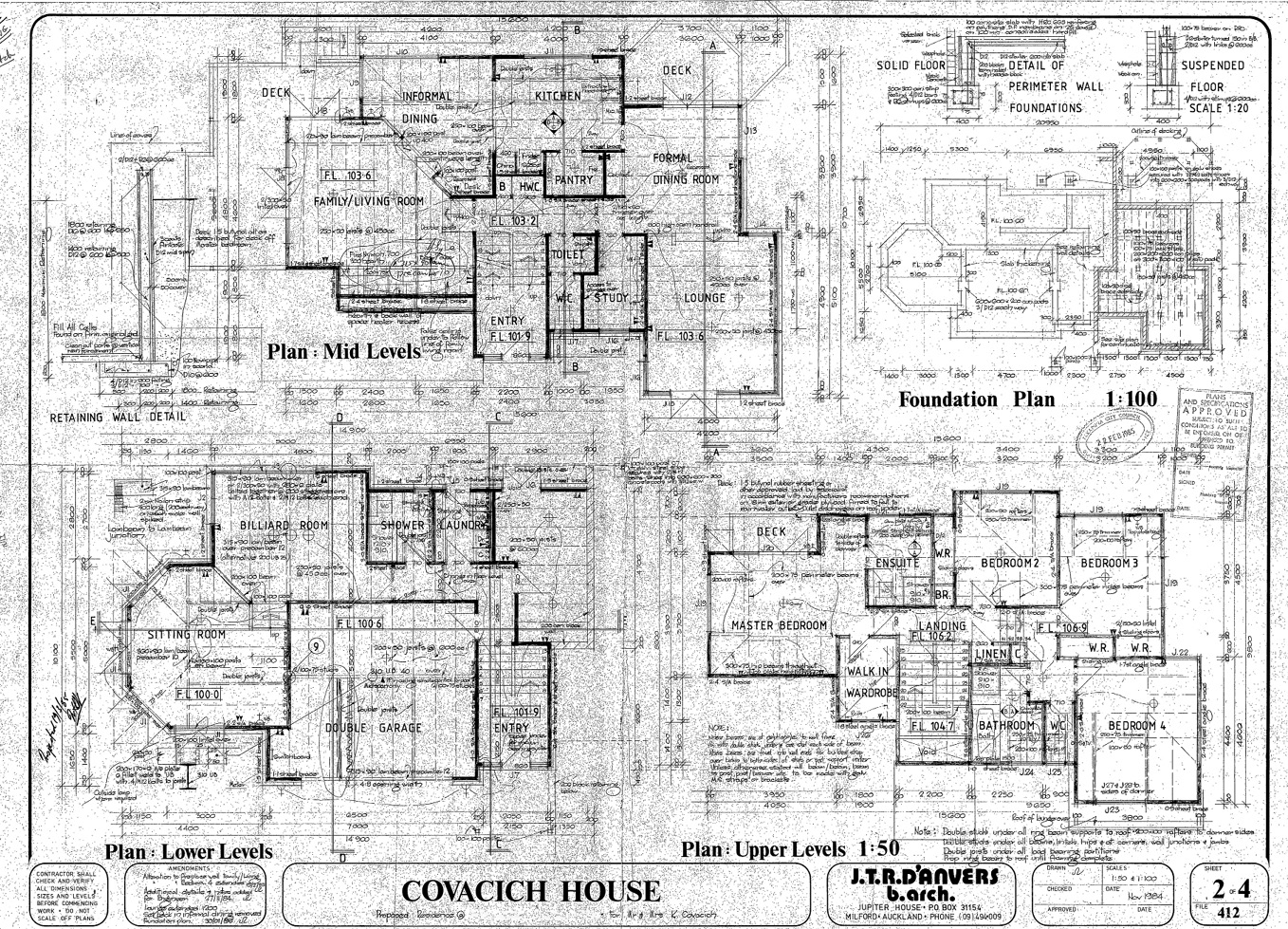

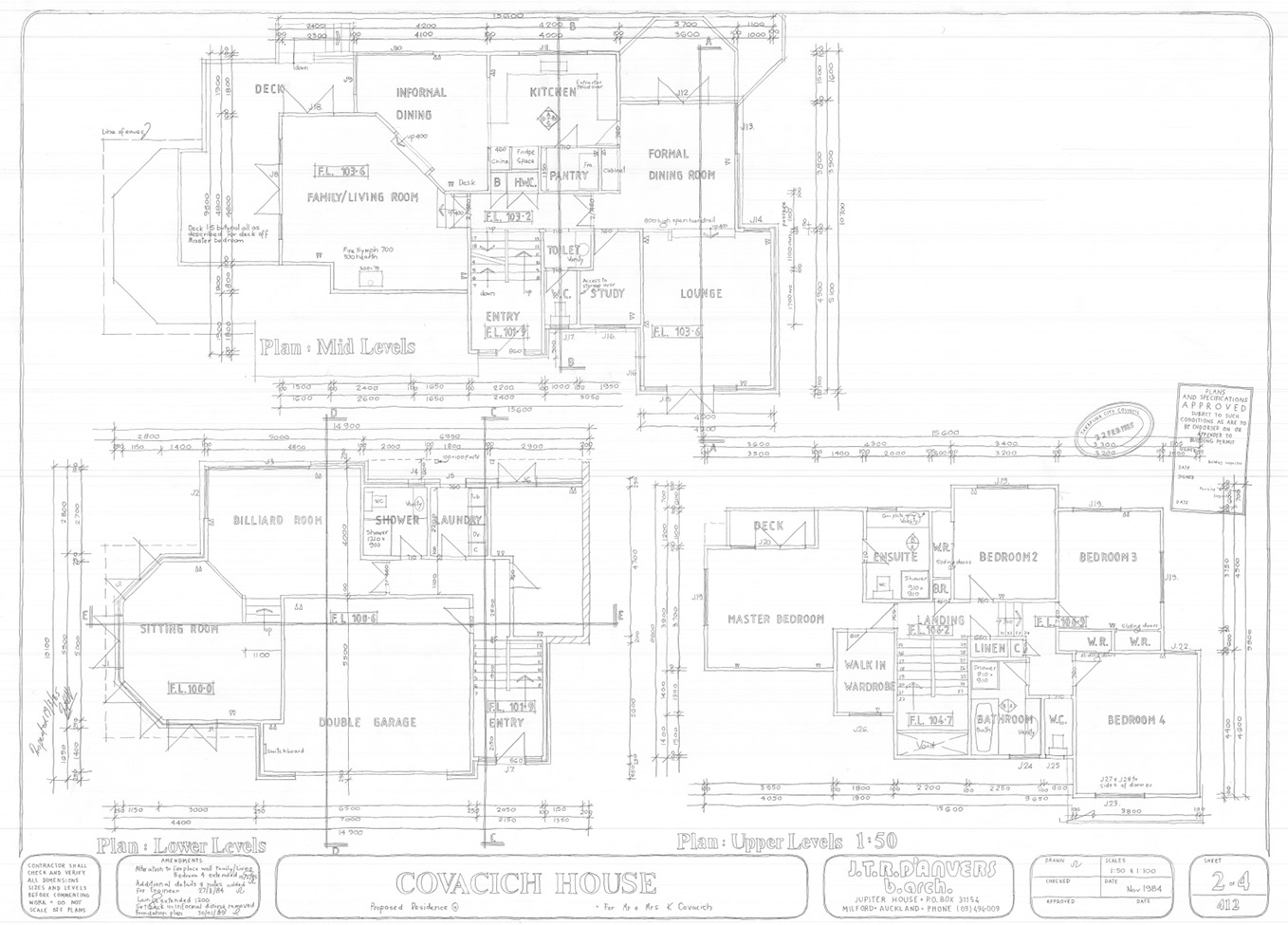

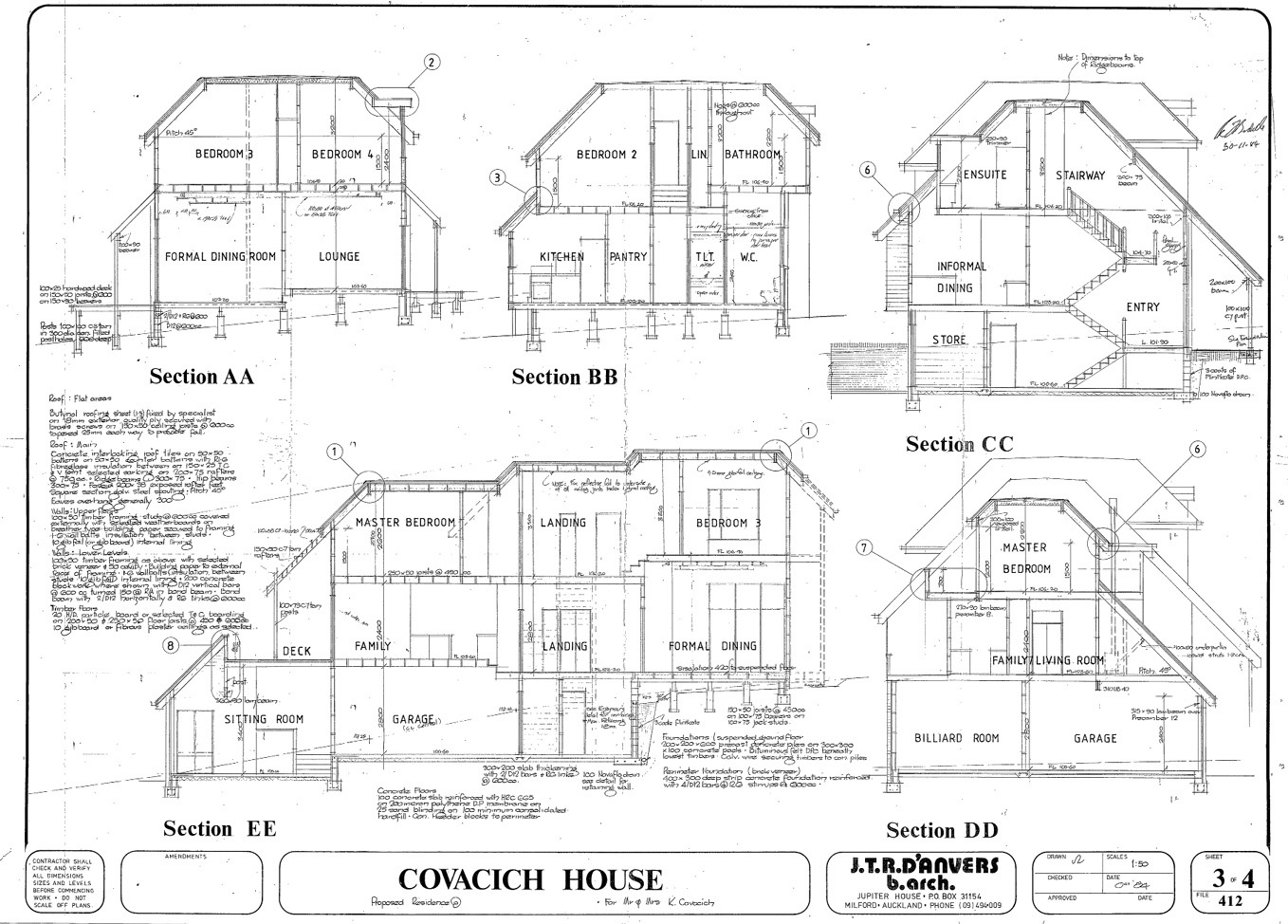

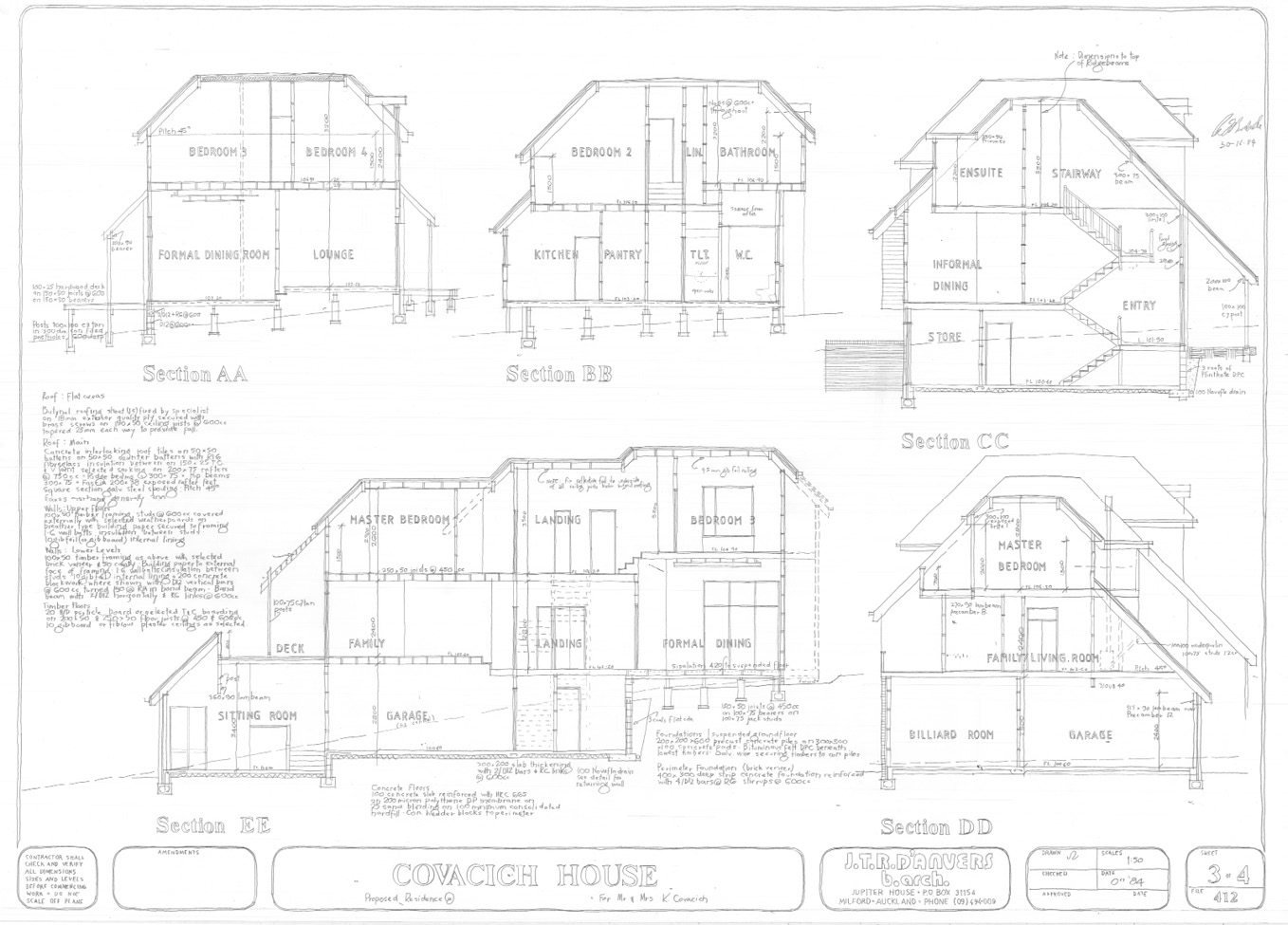

I turned to architectural drawing to record the specificity of my particular normal, using D’Anvers original documentation as my start-ing point. Since the drawings had survived only in the form of poor photocopies, I began by producing a copy of the building consent plans and sections. These were identical to the originals but omitted the messy marks and unintelligible sketches of the scanned documentation.

Fig. 5. Detail of redrawn plan (opposite).

11

12

13

Fig. 6. The scanned original plans of the house.

15

14

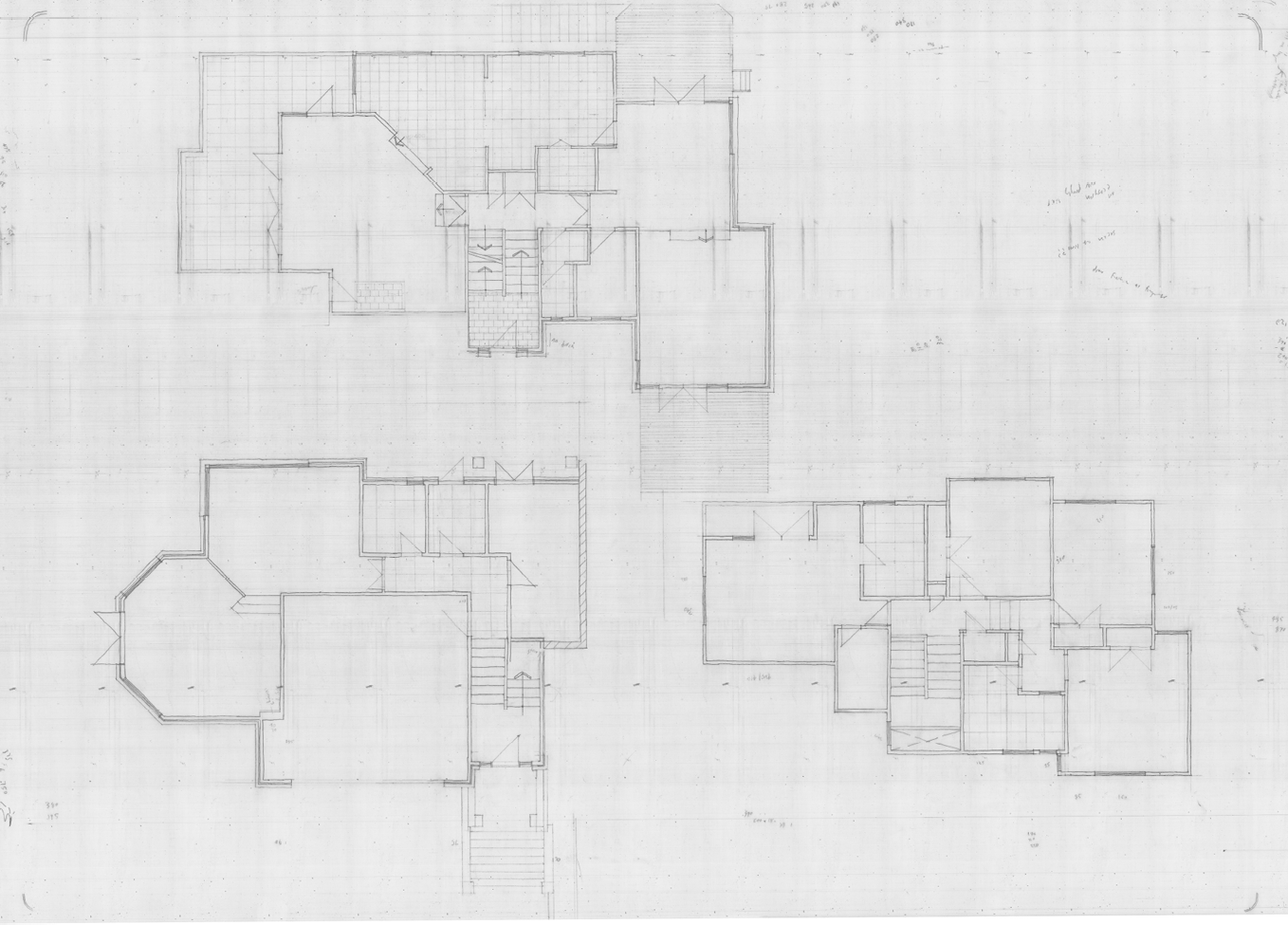

Fig. 7. My first redrawing of the plans, a direct copy of the original.

17

16

Fig. 8. The scanned original sections of the house.

19

18

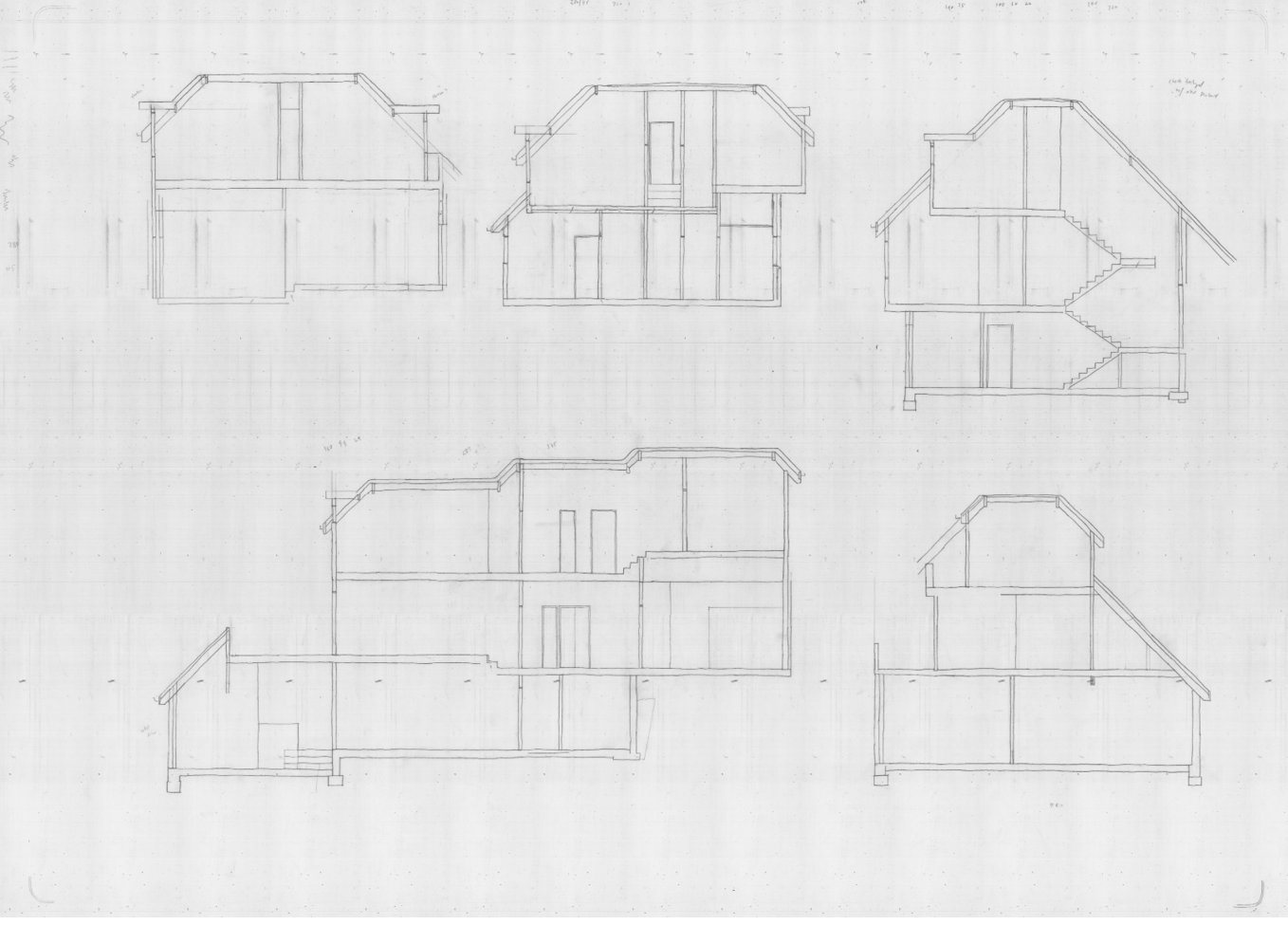

Fig. 9. My first redrawing of the sections, a direct copy of the original.

20

The re-drawing was made by tracing over the original drawings using a lightbox or a window, a time-consuming process that made me engage with the building in a new way — not the close familiarity of the resident, but the holistic vision of the architect. It was as though I was impersonating the draughtsperson who originally drew the plans, a slight iteration of the drawings forty years after the previous.

It was slightly disconcerting to describe in the detached way of the architect spaces that were almost, but not quite, those I knew so well. As I drew, I noticed discrepancies between the original drawings and the house as it exists today. A few rooms were slightly larger, a window was missing here and there and some of the spaces were labelled with functions that do not match their current use. Some of the changes must have been made during construction, while others had been made later on, sometime between its completion in 1985 and today.

I produced another copy of the drawings to reflect these changes. This time, I drew within the house itself, moving from room to room, measuring each space using a tape measure and then transcribing this information onto the page. While comparing the measurements to the original drawings, I continued to notice additional changes — the resi-due of the numerous families who have lived in the house, decorating rooms, arranging furniture, breaking things, renovating and adapting.

21

Fig. 10. Redrawing the plans a second time from within the house.

22

23

Fig. 11. My second redrawing of the plans, altering them to match the house as it exists today.

24

25

Fig. 12. My second redrawing of the sections, altering them to match the house as it exists today.

27

The Myth of Completion

Chapter 2

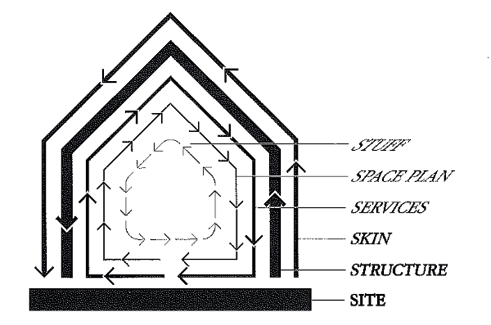

As buildings are inhabited, a gap opens up between the building and the needs and desires of those using it. To close this gap (and avoid obsolescence), we alter, tweak, add and remove. These changes happen across a range of temporal and spatial scales. In his book How Buildings Learn, American writer Stewart Brand conceives of buildings as made up of six different layers (site, structure, services, space plan and stuff), which change at different rates. The structure and skin of a building are normally altered only during a substantial renovation, while the ‘stuff’ (its furniture and objects) changes almost constantly.13

Changes in buildings over time are most evident in the duplicated homes of suburban developments. While at first these changes might be limited to a newly painted front door or an extended washing line, in a more developed neighbourhood, new conservatories, extensions and decks begin to emerge from the original whole. A particularly evident example of this change can be seen in Le Corbusier’s Les Quartiers

Fig. 13. Stewart Brand’s shearing layers of change.

28

Modernes Frugès, a 1924 experiment in standardised low-cost hous-ing in Bordeaux.14 Over four decades, the residents made significant changes to the houses, adding pitched roofs and decorative window boxes, painting the exteriors and enclosing roof terraces and garages.15 The open plan and flexible space had inadvertently created the condi-tions for easy adaptation.

Fig. 14. Altered houses in Les Quartiers Modernes Frugès.